Why Your Next Home Should be a Hotel

The residential hotel is a housing idea and way of life that deserves revisiting.

When I tell people I am a housing expert with a focus on affordability, homeless housing, and climate adaptation, they tend to ask me, “what can be done to fix these problems?” I used to have lots of answers: micro-apartments, modular construction, ADUs, coliving, cohousing, CLT (cross laminated timber), CLTs (community land trusts), flexible zoning, etc. I don’t do that any more. Nowadays, I reply that we have all the technology and know-how to fix housing-related problems, but as long as housing is treated primarily as a financial product and commodity, not a product for promoting human flourishing and ecological balance, all corrective measures will be for naught. As I suggested yesterday, the barriers to building affordable, social, dignified, equitable, and sustainable housing are moral, not technological or regulatory. With that big caveat out of the way, if I could do one thing to improve housing today, I’d make the residential hotel a mainstay of real estate once again.

The residential hotel is what it sounds like: a hotel you can live in. Until the end of WWII, residential hotels —and their down-market siblings, the rooming and boarding house —were a popular form of housing found in cities big and small alike. Guests could stay a night or a year, and there were residential hotels catering to the top and bottom of the socioeconomic ladder, though most were cheap and often run-down. America’s post-WWII suburban migration and urban renewal initiatives largely killed the residential hotel, but they did not kill the hotel’s utility and societal value. In many ways, today’s homeless epidemic and affordability crisis are downstream impacts of the loss of the flexible, low-cost, centrally located housing residential hotels once provided. With minor regulatory tweaks and zero new construction, residential hotels could rapidly be brought back to housing markets.

I researched and wrote the following piece for a client in early 2017, and though its ending sounds like it was written by a PR consultant (it was), I think I did a good job explaining the merits of hotel living in the first part. I did such a good job, a couple years after writing it, California implemented (profoundly corrupt) hotel-based homeless housing programs dubbed Project Roomkey and Project Homekey. Other states and cities (especially NYC) rolled out similar programs to house their swelling homeless populations. Unfortunately, these programs did far more to enrich owners of vacant hotels and homeless service nonprofits than provide market rate affordable housing whose absence is driving the homeless epidemic. This greedy spin on my thesis notwithstanding, the idea remains a good one. Check out my piece for an explanation of why. If you want to dig deeper into the topic, I’d also check out Paul Groth’s Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States (full text online), probably the most comprehensive history of the American residential hotel.

Reinventing the Residential Hotel: One Way to Help Solve the Housing Crisis Affecting San Francisco and other American Cities

The housing crisis facing San Francisco and many other American cities — driven by changing demographics, a booming economy, and high development costs — may be addressed by creating an alternative to the disappearing residential hotels.

For much of American history, the residential hotel served a vital need, providing basic, market-rate, affordable urban housing. Located in central locations, residential hotels served tens of thousands of people of varied means and backgrounds. But starting in the second half of the 20th century, cities began systematically destroying residential hotels. As these dwellings disappeared, waves of displaced citizens found themselves squeezed by the high cost of conventional housing.

A combination of modern conditions affecting urban populations presents a compelling case for introducing an alternative to the residential hotel. Chief among those conditions are:

Demography: Record numbers of highly mobile, single people are in need of flexible, affordable housing.

Economy: The large number of jobs in urban areas, combined with a severe housing shortage, has led to astronomical real estate prices. These conditions have created a critical need to rapidly increase the housing supply for single workers. Increasing housing options for singles can free up larger units for families, and reduce the housing costs across all segments.

Technology: Advances in modular, prefabricated construction can produce a new type of safe, high quality residences that can be built rapidly and economically.

San Francisco is a city that once abounded with residential hotels, many of which were destroyed or repurposed in the last 60 years. Replacing and redesigning these lost hotel units would greatly help to relieve its current housing crisis.

Using San Francisco as a case study, this paper examines the historic role of residential hotels, their decline and disappearance, and how the introduction of an alternative might provide safe, convenient and affordable housing to singles in San Francisco and other major cities.

History

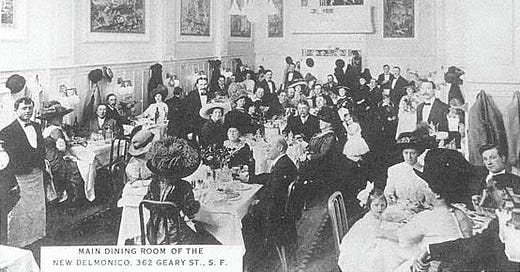

Residential hotels have existed for most of America’s history. Called rooming houses, boarding houses or simply hotels, residential hotels typically provided an affordable small room and shared bathroom. Meals were often provided in a common dining area.

Residential hotels came into prominence in the mid-to-late 19th century. In the seminal text on the subject, Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States, Paul Groth writes, “In the young Chicago of 1844, about one person in six listed in the city directory lived in a hotel, and another one in four lived in a boardinghouse or with an employer. Walt Whitman reported in 1856 that almost three-fourths of middle and upper class New Yorkers were either boarders or permanent hotel guests.

Continue reading on Medium.com.

Song of the day: