The History of the Future

Reflections on Yom Kippur and effectively dealing with the past, present, and future.

‘The longer you can look back, the farther you can look forward.’

—Winston Churchill

Sundown on Monday marked the end of Yom Kippur, Judaism’s highest High Holiday. Coming a week after Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year, Yom Kippur is often known as the day of atonement —a day to clear away the previous year’s misdeeds, so one can fulfill the aspirations of the coming year. Yom Kippur is a solemn day of prayer and contemplation about where we missed the mark —where selfishness, anger, and greed won out against compassion, kindness, and generosity in the previous year(s). To aid this contemplation, observant Jews refrain from eating and drinking as a way to directly experience the kind of suffering they may have had a part in causing others. For a variety of reasons —not least of which is my nascent journey to converting to Judaism —I observed Yom Kippur this year, and the rabbi leading the Yom Kippur services I attended started with the Churchill quote above, which is apropos of many things.

Among other reasons, my interest in converting to Judaism is borne of the question: how and why did I get here? Humans tend to attribute their circumstances , for good or ill, to the forces of their lifetimes. For example, I am dismayed about my current personal and professional circumstances—no contact with my kids, being a pariah in an industry I was once an authority in, and so forth —and it’s tempting to blame these circumstances to living people and current affairs. But as I’ve written about before, current effects (what’s happening) flow from previous causes (why what’s happening is happening), and many of these causes precede our births, whether those causes be genetic, economic, cultural, or environmental in nature. Transgenerational causes —a family’s traits and traumas that reach across multiple generations —have a particularly dominant role in shaping the effects of our lives. Put another way, most of us are enjoying the fruits and dealing with the crap our forebears left us.

Using my past as access to the present and future was reinforced during the lockdown, when I deep dove into my family history, abetted by my grandfather’s self-published memoir and trial sessions on several genealogy sites. Through these explorations, I realized my life bore striking similarities to many of the men in my clan, and that my experiences were part of a genetic and cultural continuum.

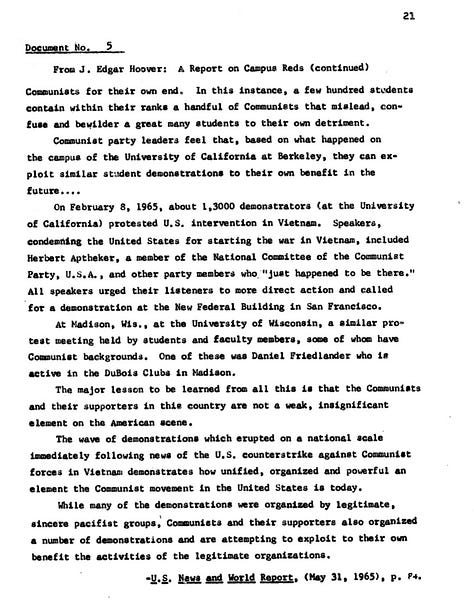

The men in my family* are known for their intelligence, independence of thought, and literal death grip on lofty ideals and principles. I’ve written here before about my dad, grandfather Ben, great-grandfather Israel, and my other great-grandfather, Isak Straus —the former two men experienced years of persecution for their moral and political convictions and the latter two died for them. From this intellectual, political, genetic, and spiritual ooze I emerged, seemingly fated to be persecuted, dismissed, exiled, and posthumously revered, though I’m doing my utmost to bend the arc of history.

The dissidence with the societies the men in my family inhabited was informed and exaggerated by their Jewishness, people who have existed as outsiders inside larger societal contexts for time immemorial. Therefore, it’s hard to understand my family and personal histories without understanding Jewish history.

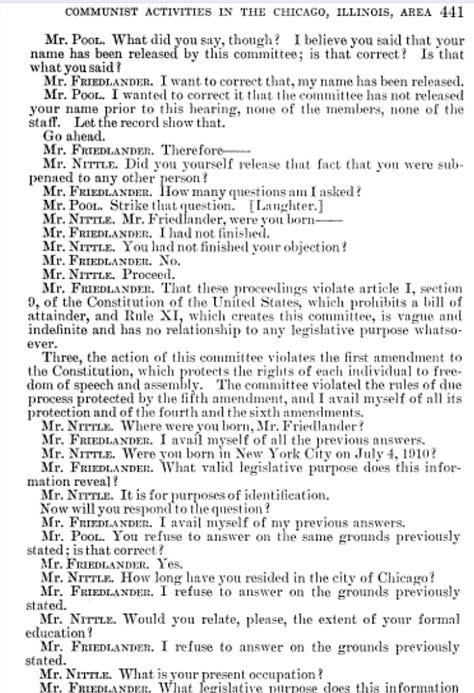

In my erstwhile industrial niche, housing innovation, my credibility and paychecks depended on my ability to predict the future —forecasting the social, economic, environmental conditions coming down the pike and highlighting the technological, operational, and economic interventions to meet those conditions. Starting in 2019, my forecasts became too bleak and interventions too intensive for status quo stakeholders to hear or accept. In true Friedlander fashion, my prognostications were ignored and I was effectively exiled —aka ‘canceled’ —from any position of influence. My situation in the context of my family history makes me recall The Onion headline, “History sighs, repeats itself.”

To be sure, my bleak prognostications about the current state and future of housing —and about society writ large —have historical causes.

After breaking my Yom Kippur fast and spending the day contemplating my transgressions and praying for God’s mercy, I went home and put Youtube on in hopes of enjoying some lighter fare. Instead, I put on Dances with Wolves, which I’ve been slowly watching the last week, and also happens to directly relate to the Churchill quote and Yom Kippur.

Dances with Wolves is corny in places. For example, it’s ostensibly about indigenous Americans, but centered on two white people, one of whom is improbably a member of an indigenous tribe. But the movie is an effective reminder of the cultural, economic, political, and environmental foundation from which modern America emerged.

America is an empire largely built with slave labor on stolen land. For around 400 years, colonialists and later American political and commercial stakeholders have exploited labor and land as much and as fast as they could before discarding and replacing the old with new labor and lands; this unholy cycle seems to be hitting a crescendo as the availability of exploitable labor and land diminishes, but it’s still the core of the country’s business model. In light of this violent foundation, it’s logical that America’s culture, economy, and environment is in such a pitiful state. But all efforts to solve the country’s problems —to create the conditions for socioeconomic and racial equity, to achieve environmental sustainability and restoration —are useless until there is an acknowledgment and reckoning (i.e. atoning) of past sins. Beyond random chatter about reparations, there’s little to suggest this will happen to the degree it needs to.

It’s a damn shame we as a society won’t acknowledge and reckon with history, because it fates us to keep trying new spins on the same old bullshit. Just as new year hopes are on the other side of reckoning with last year's transgressions, a happy, healthy, sustainable future is on the other side of reckoning with past violations. In the meantime, I’m focusing on my own damn self, righting my own past wrongs and getting very clear about where I come from, because in each new layer of understanding of my history there’s a new entry point into the future.

*“My family” here refers to my father’s family, whose outsized personalities and abundant records were, and are, the dominant influences shaping my identity and perspectives. My mother’s family were Irish and Austrian Catholic immigrants, who I respectfully refer to as “boat people,” i.e. the poor and huddled masses who came to America in the late 19th century and lacked much/any documents about their provenance. I proudly carry boat people blood (and sturdy genes), but contrary to my dad’s family, I know little about this side beyond broad socioeconomic and cultural brush strokes.

Song of the day:

Connecting your personal Day of Atonement with our country's non-atonement was very interesting. I think frequently of the latter as it relates to affordable housing - everybody of course is all for affordable housing - as long as nothing changes, especially the intentionally exclusionary single-family housing rules. In Boulder we like to pass taxes and give away money, but are unwilling to change the structure that created the situation. Maybe because it's been baked in for generations.

It's remarkable that you have identified traits in common with generations of your male ancestors. And unlike the country, you are being thoughtful and aware - the pattern might not change today, but awareness is always the first step.

I was adopted so have zero knowledge of any ancestors. I'm always surprised when people express sympathy, or I hear of others launching all-out searches for their biological parents - I'm really happy about my fate! No Hatfield vs McCoys, Sunni vs Shia, Northern Ireland vs Ireland for me - I'm out of any generational fray - just be here now.