Thoughts On Israel, Part I

The genesis of a high, holy, historical mess.

My great-great grandfather, Herbert Bentwich, was a prominent English lawyer, and founded the British Zionist Federation in 1899. Along with Theodore Herzl, Herbert was part of a small but powerful group of European Jews who birthed the modern Zionist movement —one that eventually led to Israel’s nationhood in 1948. Both of my paternal great-grandfathers, Israel Friedlander and Isak Straus, were prominent Zionists who extensively traveled to Palestine in the early 20th century; their children, my grandparents, spent many years in Palestine as well and separately attended The Reali School in Haifa in the 1920s. My great-grand uncle, Norman Bentwich, was the Attorney General of British Mandate Palestine, the name given to the British-controlled state that preceded Israel’s nationhood. My great uncle (through marriage), Shimon Agranat, was the third president of Israel’s Supreme Court. My father later spent time in Israel as a young man and lived on a kibbutz, as I would do several decades later.

I cannot speak to all the discrete motivations my family members had in supporting a Jewish state, though my great-grandfather Israel is on record for expressing his desire to establish a state that was a union of religion and nationalism. A scholar of Arab and Semitic languages, he saw Israel as an opportunity to be a “Land of Promise, not only to the Jew but to the entire world —the promise of a higher and better social order.”

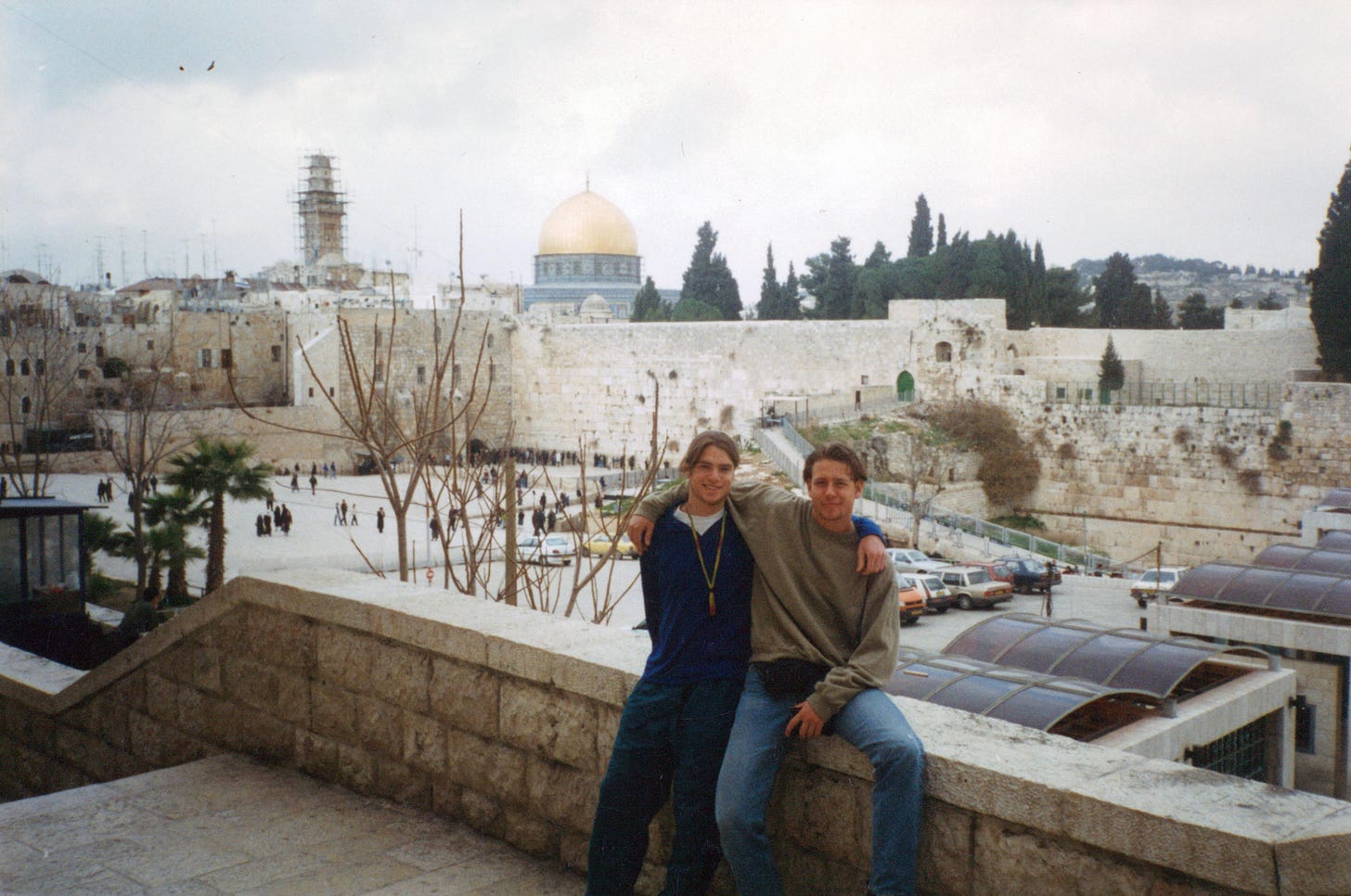

When I visited Israel in 1995, I was guided by a desire to understand my ancestry and perhaps find my own homeland. Besides my time at the kibbutz in Galilee, I spent time in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and at a former family estate outside Haifa. While there were many aspects of the country I enjoyed —Jerusalem’s historical fecundity, the amazing falafel stands —my overwhelming impression of Israel was of a place defined by conflict. My trip was less than two months after the assassination of prime minister Yitzhak Rabin by a hard-right Jewish radical who opposed Rabin’s participation in the Oslo Peace Accords. When I visited my great-aunt Carmel (Agranat) who lived near the Knesset in Jerusalem, I had to navigate past a rally by Ethiopian Jews protesting their mistreatment by white Israelis. A bus line I regularly took in Tel Aviv was bombed not long after I left the country. I spent a couple nights in a bomb shelter at my kibbutz because an Islamic faction on the nearby Lebanese border was firing mortars onto our compound. Everywhere, people seemed to be arguing, which I found to be a conversational style evident with Israelis in and out of their home country. Rather than feeling an ancestral connection to stay in Israel, I felt an urge to leave before I got caught in any crossfire. The recent attacks by Hamas on Israel and Israel’s response, while horrific, are unsurprising in this fraught atmosphere.

The modern nation (i.e. country) is largely a 19th and 20th century construct —one borne of colonialist interests, industrial and technological advancements, and romantic notions about platonic national identities. Prior to the 19th century, nations like Germany and Italy were regions containing several independent principalities. Today’s nations in South America, Africa, and Asia were largely formed to establish discrete territorial zones for their colonial overlords. Yes, centralized imperial power and some nations that exist today existed prior to the 19th century, but without phones, motorized transit, and other geography-shrinking technology, the ability to control territories distant from the imperial or national seat of power was limited, and most preindustrial power structures across the globe were decentralized and organized around clans, tribes, villages, kingdoms, and small city-states.

The colonial imposition of nationhood on decentralized regions and cultures was particularly true of the Middle East, which Thomas Friedman explains in his 1989 book, From Beirut to Jerusalem:

In the wake of World War I, however, the British and French took out their imperial pens and carved up what remained of the Ottoman dynastic empire, and created an assortment of nation-states in the Middle East modeled along their own. The borders of these new states consisted of neat polygons—with right angles that were always in sharp contrast to the chaotic reality on the ground. In the Middle East, modern Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Palestine, Jordan and the various Persian Gulf oil states all traced their shapes and origins back to this process; even most of their names were imposed by outsiders. In other words, many of the states in the Middle East today—Egypt being the most notable exception—were not willed into existence by their own people or developed organically out of a common historical memory.

But this imposition of statehood did not undo thousands of years of cultural evolution in which dispersed tribes competed for the desert region’s limited resources. Again, from Friedman:

The first and oldest of these [Middle East] traditions is tribe-like politics. I use the term “tribe-like” to refer to a pre-modern form of political interaction characterized by a harsh, survivalist quality and an adherence to certain intense primordial or kin-group forms of allegiance. Sometimes the tribe-like group that is in power in the Middle East, or is seeking power, is an actual tribe, sometimes it is a clan, members of a religious sect, a village group, a regional group; sometimes it is friends from a certain neighborhood, an army unit, and sometimes it is a combination of these groups. What all these associations have in common is the fact that their members are all bound together by a tribe-like spirit of solidarity, a total obligation to one another, and a mutual loyalty that takes precedence over allegiances to the wider national community or nation-state.

So Israel’s 1948 statehood was the imposition of modern nationhood on a region historically governed by tribes, clans, and hamstrung imperial forces (chiefly Ottomans). Unlike other modern Middle Eastern nations, Israel nationhood didn’t just impose statehood on an existing population. Between 1948 and 1952, about 740,000 Jewish immigrants, mostly from Europe, moved to Israel, displacing 1.4 million Muslims Palestinians, half of whom were forced from their towns and homes practically overnight, sent to Gaza, West Bank, and to countries around the world. Just as I theorized how the US is still paying the price for the genocide of indigenous populations, Israel is paying the price of its displacement of and violence towards Palestinian populations.

To be continued [after I figure out my point and write it out]….

You have major credibility in order to address this issue; interesting to see what you follow with. As for me, I'm reminded of (a distortion of) the Golden Rule: "Do unto others as others have done unto you."